How 'vaccine passports' could exacerbate global inequities

Author: By Andrew Green // 19 April 2021

How 'vaccine passports' could exacerbate global inequities

Kenyan officials accused the United Kingdom of “vaccine apartheid” this month after London added the East African country to its “red list” — the 39 countries where the U.K. bars entry to anyone who’s been within their borders in the previous 10 days. The vast majority are in Latin America and Africa, including countries such as Rwanda, which have done significantly better at controlling the spread of the pandemic than the U.K.

British officials say the ban is necessary to prevent the introduction of COVID-19 variants. Kenyan officials saw it as an example of a high-income country using the pandemic to discriminate — and slapped a two-week quarantine on all passengers from or transiting through the U.K.

Experts say that this clash over people’s ability to move could pale in comparison to the disruptions that will be caused by the potential introduction of “vaccine passports.” And the emerging efforts to restrict people’s movements based on whether they have received a COVID-19 vaccine are heightening concerns about inequities that have already been revealed or exacerbated by the pandemic.

To begin with, Joia Mukherjee, chief medical officer of social justice nonprofit Partners in Health, said most people in the global south have not even been offered a vaccine. Of the 841 million vaccine doses that had been administered by Thursday, only 0.1% had gone to people in low-income countries.

“There really shouldn’t be anything until we can ensure equitable access for the vaccine,” she said. “Otherwise we are creating another superstructure or colonial hierarchy of people from wealthier countries having access and poorer countries not having access.”

If that hierarchy is sanctioned and citizens of low-income countries are denied access, vaccine passport critics warn, it will sharpen a global divide created by a few high-income countries hoarding the world’s vaccine supply — and in so doing, blocking unvaccinated people from having access to goods and knowledge, even as their counterparts from higher-income countries get a jumpstart on recovery.

“The necessity of decolonization is making sure that local expertise is recognized and enhanced and empowered in a way to mitigate the harm that would be done by this global downturn.”

— Joia Mukherjee, chief medical officer, Partners in Health

In the discussion over vaccine passports, it is important to distinguish what is even being debated, Matthew Kavanagh, director of the Global Health Policy and Politics Initiative at Georgetown University, told Devex. Some countries, like Israel, are introducing domestic regulations that allow vaccinated people to gain access to spaces, such as gyms and restaurants that are barred to people who have not been immunized.

Other countries, including Estonia and Iceland, are beginning to allow people within their borders as long as those travelers can prove they have been vaccinated. The European Union and the United States are both investigating how to create standards for people to prove vaccination status.

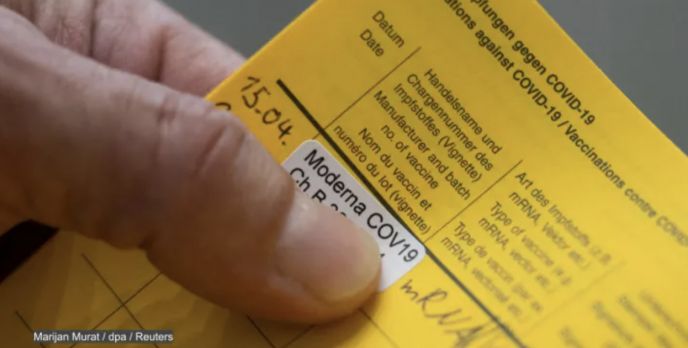

Kavanagh said there are equity issues with both approaches. That includes questions of whether vaccines have been fairly distributed to all communities, as well as what form the vaccine passport or record actually takes. If countries or international agencies settle on a digital record, for instance, people without access to smartphones may suffer.

It could also fuel a rise in efforts to fake the passports, like the underground market in counterfeit yellow fever certificates that exists in Nigeria’s Lagos airport, where fake cards cost as little as $8.50.

But the broader restriction on who is allowed to travel regionally and internationally, specifically, may ultimately “compound the economic harm of the COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries and keep students, scientists, and many others from participating in the globalized world, potentially for years to come,” Kavanagh said.

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have joined in the effort to push back against a vaccine passport, with WHO Spokeswoman Margaret Harris citing uncertainties about whether the vaccine prevents transmission, as well as concerns about equity.

John Nkengasong, director at Africa CDC, was even more straightforward at a recent press briefing. “Our position is very simple,” he said. “That any imposition of a vaccination passport will create huge inequities and will further exacerbate them.”

Passport proponents have pointed to existing vaccine entry requirements to justify the new measures, the most prominent being the yellow fever vaccinations required by some countries, displayed on conspicuous yellow cards. But Mukherjee dismissed the comparison, pointing out that yellow fever vaccinations are widely available, including at points of entry to countries that require them.

“It doesn’t have the built-in scarcity we see in the COVID vaccine that’s created by the limited production of pharmaceutical manufacturers,” she said. “We should really expand access as a priority, not restrict travel.”

Nationalism has so far governed the vaccine distribution, though, and there are fears it will also guide calls for vaccine passports, as citizens of vaccinated countries began to demand access to the rest of the world. That has only bolstered the efforts of PIH and others to lobby for vaccine equity.

That includes an ongoing push for the proposal by South Africa and India at the World Trade Organization to temporarily suspend intellectual property rights for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Higher-income countries, including the U.S. and U.K., oppose the proposal and have thus far been able to sideline it at the WTO.

The debate puts some organizations contributing to the development of LMICs and engaging in calls for vaccine equity in a potentially difficult position, though. Aid agencies often shuttle in outside employees, particularly senior officials, to work on projects.

In a world of vaccine passports, those positions could only be filled by people who have had access to immunizations. Or NGOs and agencies could facilitate vaccinations for their own employees, but risk contributing to domestic inequalities.

Alternatively, Mukherjee said, if organizations are committed to equity, they could continue to call for improved vaccine access even as they seize on the opportunity to train and elevate employees from within the country. That is particularly true, she said, at a time when so many countries from the global south have mounted a stronger response to COVID-19 than countries such as the U.S.

“The necessity of decolonization is making sure that local expertise is recognized and enhanced and empowered in a way to mitigate the harm that would be done by this global downturn,” she said.

The pandemic has already brought those efforts to the fore, including a call early in the pandemic from InterAction, a hub for NGOs working on global poverty, to accelerate localization efforts.

“Ironically, one small silver lining to the pandemic has been that with travel restricted, in a few countries I have seen national staff in development agencies gain increasing power and autonomy,” Kavanagh said.

PIH had already committed to hiring the vast majority of their staff members from the countries where their projects are based before the pandemic began. But Mukherjee said COVID-19 only reinforced that decision: “You can do a lot without getting on an airplane.”